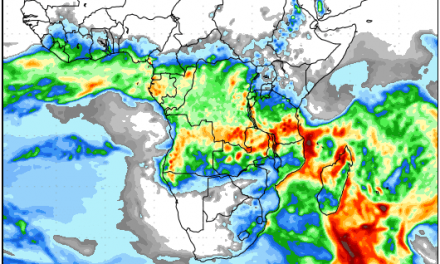

The Week’s Weather up to Friday 17 November. Five-day outlook to Wednesday 22 November 2017

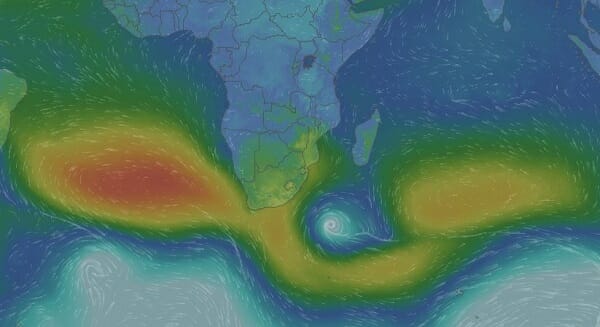

Map: Animated progressive map of southern Africa surface pressure and wind flow on Friday 17 November 2017. Source: https://www.windy.com/?pressure,-2.548,52.734,3

An understanding of the South Atlantic high pressure cell is essential to understand what transpired weatherwise this week.

As is evident from the coloured synoptic map, the South Atlantic high is a formidable weather phenomenon, arguably the single biggest driver of Namibia’s weather. The local impact of all other elements are defined by the relative strength and the physical locality of this high.

The areas marked in yellow are the outer perimeter of the highs. Barometric pressure at this isobar is usually about 1020 mB. The area marked in red is the high’s core, usually with a pressure not lower than 1024 mB. The areas marked in green are the transition zones ranging in pressure from about 1016 mB to 1012 mB. The blue areas are lower pressure (less than 1012 mB while the white indicates a fully developed low pressure system, either a trough (less than 1008 mB) or a proper vortex, around 1000 mB or even slightly less.

The image shows that the South Atlantic high, for this week, was stronger than the southern Indian high. In between, a long ridge extended which is an extension of the South Atlantic high as it migrates around the southern Cape before morphing into the southern Indian high. This is normal and it happens all the time. The high pressure cells never stop their journey from west to east all around the southern hemisphere in the so-called high pressure belt between 25°S and 40°S latitude.

The image also shows that a prominent low pressure vortex was present south of Madagascar, similar to last week. This low pressure system is a result of the interaction between the trailing edge of the southern Indian high, and the leading edge of the South Atlantic high. What it does is to reduce the South Atlantic high’s strength as it moves around the southern Cape often leading to a collapse of the southern Indian high as it splits off from the South Atlantic high.

Also visible, is the enormous extent of the South Atlantic high. It covers almost the entire ocean between Africa and South America. When it is in this position, it drives the so-called trade winds.

These follow the South Atlantic high’s leading edge from south to north, and then across the ocean from Cape Town to the mouth of the Amazon River. On the trailing edge, the direction is reversed, stretching from the South American mainland on a trajectory much further south to a position about 1000 km south-west of Cape Town. These winds are called trade winds as they propelled the ships that sailed from Europe to the Far East from the 1500s onward. It was easier to sail to the Caribbean first, and then on the back of the South Atlantic high, to the Cape of Good Hope. Trying to sail against the south-easter on the northern rim of the South Atlantic high was a futile exercise.

Along the South Atlantic high’s leading edge, due to the relative position of its core, winds blow from south to north. These winds advect cold air from the Antarctic circle northward to the African continent. In winter they bring icy conditions to Namibia and snow to the southern Cape and the Drakensberg. When they are active early summer, as this past week, it indicates that the South Atlantic high is very strong, very active, and displaced further northward than usual.

This is not a unique occurrence. It often happens during the transition phase from winter to summer but the effect gets less and less as the sea surface temperature in the South Atlantic increases slightly in summer. A northwardly displaced South Atlantic high indicates colder sea surface temperatures, an observation that is easily corroborated by looking a satellite images based on refraction.

In Namibia, the South Atlantic high is the reason for the existence of both the Namib and the Kalahari deserts. When the high makes it presence felt like it did this week with the cold intrusion, it is just a confirmation that basically all Namibian weather is to a lesser or greater degree dependent on the vagaries of the South Atlantic high. It is so powerful, it clears the continent of moisture as far as southern Angola, Western Zambia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, and the entire South Africa above the escarpment.

Only once the South Atlantic high weakens by about 4 millibars and its core shifts to the south by about 1000 km, does the rainy season in the western half of southern Africa start.

What’s coming

During Saturday and Sunday, the extension between the two high pressure cells, splits in two, making some space for lower pressure over the sub-continent. This is amplified by the daily solar heating of the land surface. Normal early summer weather returns to Namibia with the wind flow reverting to a northerly direction.

Monday sees a brief repeat of this week’s cold intrusion when another cold front ahead of the South Atlantic high crosses from Saldanha Bay to Port Elizabeth. The northward impact should be limited to the Karas Region.

By Tuesday, Namibia is split along the signature convergence zone running from Ruacana across the interior to Ariamsvlei. The south-western quadrant will be cool to warm with fresh winds along the escarpment, while the north-eastern quadrant will be hot to very hot, with a pronounced air flow from the north.

By Wednesday a mid-level trough has formed from southern Angola, across the Kavangoes, into Botswana, bringing prospects of light rain in Kavango West, Kavango East, eastern Otjozondjupa and northern Omaheke.