Extracting power and self-enrichment from state resources – the foundation of corruption

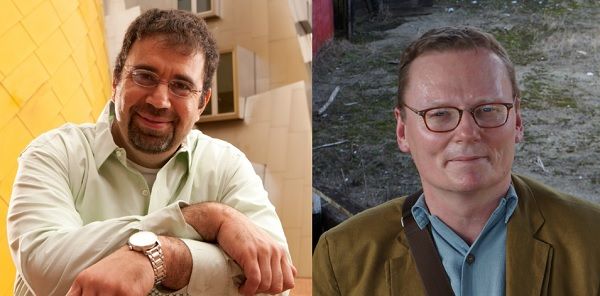

By Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson.

Daron Acemoglu is Professor of Economics at MIT. James A. Robinson is Professor of Global Conflict at the University of Chicago. They are the co-authors of The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty.

CAMBRIDGE – In the euphoric moment immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union, few would have guessed that Ukraine – an industrialized country with an educated workforce and vast natural resources – would suffer stagnation for the next 28 years. Neighboring Poland, which was poorer than Ukraine in 1991, managed almost to triple its per capita GDP (in purchasing power parity) over the next three decades.

Most Ukrainians know why they fell behind: their country is among the most corrupt in the world. But corruption does not emerge from thin air, so the real question is what causes it.

As in the other Soviet republics, power in Ukraine was long concentrated in the hands of Communist Party elites, who were often appointed by the Kremlin. But the Ukrainian Communist Party was very much a transplant of the Russian Communist Party itself, and regularly operated at the expense of indigenous Ukrainians.

Moreover, as in most of the other former Soviet republics (with the notable exception of the Baltic countries), Ukraine’s transition away from communism was led by former communist elites who had reinvented themselves as nationalist leaders. This did not work out well anywhere. But in Ukraine’s case, the situation has been made worse by a constant struggle for power between rival communist elites and the oligarchs they helped create and propagate.

Because of the dominance of various warring factions, Ukraine has been captured by what we called extractive institutions: social arrangements there empower a narrow segment of society and deprive the rest of a political voice. By permanently tilting the economic playing field, these arrangements have long discouraged the investment and innovation needed for sustained growth.

Corruption cannot be understood without comprehending this broader institutional context. Even if graft and self-dealing in Ukraine had been controlled, extractive institutions still would have stood in the way of growth. That’s what happened in Cuba, for example, where Fidel Castro took power and put a lid on the previous regime’s corruption, but set up a different type of extractive system. Like a secondary infection, corruption amplifies the inefficiencies created by extractive institutions. And this infection has been particularly virulent in Ukraine, owing to the complete loss of trust in institutions.

Modern societies rely on a complex web of institutions to adjudicate disputes, regulate markets, and allocate resources. Without the trust of the public, these institutions cannot serve their proper function. Once ordinary citizens start assuming that success depends on connections and bribes, that assumption becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Markets become rigged, justice becomes transactional, and politicians sell themselves to the highest bidder. In time, this “culture of corruption” will permeate society. In Ukraine, even universities are compromised: degrees are regularly bought and sold.

Although corruption is more of a symptom than a cause of Ukraine’s problems, the culture of corruption must be uprooted before conditions can improve. One might assume that this simply requires a strong state, with the means to root out corrupt politicians and businessmen. Alas, it is not that simple. As Chinese President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive illustrates, top-down action often becomes a witch hunt against the government’s political opponents, rather than a crackdown on malfeasance generally. Needless to say, applying a double standard is hardly an effective way of building trust.

Instead, combating corruption effectively requires the robust engagement of civil society. Success depends on improving transparency, ensuring the independence of the judiciary, and empowering ordinary citizens to kick out corrupt politicians. After all, the distinguishing feature of Poland’s post-communist transition wasn’t effective top-down leadership or the introduction of free markets. It was Polish society’s direct engagement in building the country’s post-communist institutions from the ground up.

To be sure, many of the Western economists who descended on Warsaw after the fall of the Berlin Wall advocated top-down market liberalization. But those early rounds of Western “shock therapy” resulted in widespread layoffs and bankruptcies, which provoked a broad-based societal response led by the trade unions. Poles poured into the streets, and strikes skyrocketed in frequency – from around 215 in 1990 to more than 6,000 in 1992 and more than 7,000 in 1993.

Defying Western experts, the Polish government backpedaled on its top-down policies, and instead focused on building a political consensus around a shared vision of reform. Trade unions were brought to the table, more resources were allocated to the state sector, and a new progressive income tax was introduced. It was these responses from the government that instilled trust in the post-communist institutions. And over time, it was those institutions that prevented oligarchs and the former communist elites from hijacking the transition and spreading and normalizing corruption.

By contrast, Ukraine (as well as Russia) received the full dose of top-down “privatization” and “market reform.” Without even a pretense of empowering civil society, the transition was predictably hijacked by oligarchs and the remnants of the KGB.

Is a society-wide mobilization still feasible in a country that has suffered under corrupt leaders and extractive institutions for as long as Ukraine has? The short answer is yes. Ukraine is home to a young, politically engaged population, as we saw in the Orange Revolution of 2004-2005 and in the Maidan Revolution of 2014. Equally important, the Ukrainian people understand that corruption must be uprooted in order to build better institutions. Their new president, Volodymyr Zelensky, campaigned on the promise of fighting corruption, and was elected in a landslide. He now must kick-start the cleanup process.

US President Donald Trump’s attempts to involve Ukraine in his own corrupt dealings have given Zelensky the perfect opportunity for a symbolic gesture. He should publicly refuse to deal with the Americans until they sort out their own corruption problems (even if it means turning down tainted aid).

After all, the United States is now one of the last countries that should be lecturing Ukraine about corruption. To play that role again, its courts and voters will have to make clear that the Trump administration’s malfeasance, attacks on democratic institutions, and violations of the public trust will not stand. Only then will the US be a role model worth emulating.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2019.

www.project-syndicate.org