When Yang fails, Yin is employed to solve complex problems

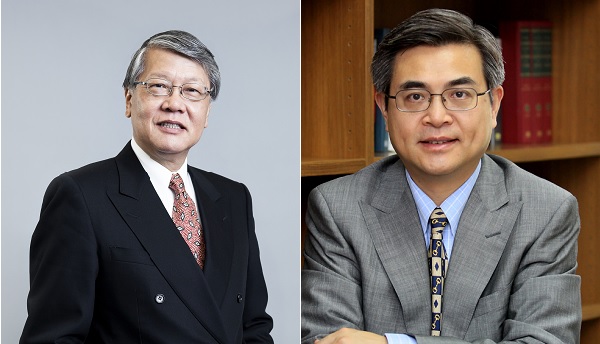

By Andrew Sheng and Xiao Geng*

Hong Kong – We live in an age of systemic gridlock, policy chaos, and sudden-shock failures. How is it possible that Afghan security forces – built and trained by the United States military at a cost of $83 billion over two decades – succumbed to a militia of fighters in pickup trucks in a mere 11 days? How could America’s best and brightest intelligence experts and military leaders have failed to foresee that the rapid withdrawal of US air support and reconnaissance would spell disaster for Afghanistan, and plan their retreat accordingly? Are these not examples of systemic failure?

Look at almost any crisis, and you will see multiple causes and drivers. That is as true for the situation in Afghanistan as it is for the COVID-19 pandemic – another multi-dimensional crisis for which there is no silver-bullet solution. Even carefully designed policies, motivated by the best of intentions, can fail to have the intended effect – and often exacerbate problems in unexpected ways – owing to implementation mistakes.

The problem can be boiled down to a complexity mismatch. The various crises and challenges we face – such as terrorism, pandemics, and disinformation – have viral, entangled qualities, and complex global networks allow locally generated problems to grow and spread much faster than solutions. Yet the paradigm on which we base our policymaking is linear, mechanical, and “rational.”

This approach can be traced back to political philosophers like Thomas Hobbes, who offered a straightforward, top-down approach to governing human society, based on “universal” truths. The Newtonian-Cartesian paradigm that guides economic thinking is similarly mechanical, pursuing a timeless, one-size-fits-all Theory of Everything.

But, while such an approach might help us to understand or govern small states or communities, it is impractical in a highly complex global system. And yet, we remain committed to it. This leaves us blind to the obvious – including our own blindness – and vulnerable to conceptual traps and collective-action problems that perpetuate indecision, inaction, and inconsistency. Without a new approach that captures the true complexity of our world, we will continue to be blindsided by systemic failures.

We should look to nature. As the biologist Stuart Kauffman has pointed out, the eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant observed that everything in nature “not only exists by means of the other parts, but is thought of as existing for the sake of the others and the whole” – that is, “as an (organic) instrument.” In other words, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and both negative and positive feedback mechanisms link the various parts that form – and transform – the whole.

If the Earth is a single living system, managing each component separately will not only be ineffective; it will have potentially disastrous unintended consequences. Likewise, in our broader global system, which includes both living and non-living parts, policies based on zero-sum logic or siloed thinking will always fall short – or worse.

A superior approach, as the late Donella Meadows argued, would be to focus on so-called leverage points in complex systems, “where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything.” Problems are not nails to be hammered, but symptoms of systemic flaws that are best addressed by acting on a range of load-bearing institutions.

This could mean, for example, making changes to subsidies, taxes, and standards; regulating negative feedback loops and encouraging positive feedback loops; improving or limiting information flows; or updating incentives, sanctions, and constraints. Crucially, it could also mean changing the mindset or paradigm from which system goals, power structures, rules, and culture arise.

Nobel laureate political scientist Elinor Ostrom also offered vital insights for managing complex systems – specifically, escaping the collective-action trap. As Ostrom explains, the trap arises from zero-sum, binary thinking. The key to avoiding it, therefore, is to create local commons comprising shared ideas, property, values, and obligations. With our fates and interests intertwined – and operating on longer time horizons – different parties are far more likely to work together to avoid the “tragedy of the commons.”

Unfortunately, the male-dominated mainstream has largely ignored Meadows’ and Ostrom’s insights. But their ideas do align with the Chinese worldview of organic materialism, as articulated by British sinologist Joseph Needham.

Like Meadows, the Chinese would “act on the underlying trend of forces” (顺势而为). And in the spirit of Ostrom, the Chinese eschew the view of the Sino-American rivalry as a zero-sum competition between Western democracy and Chinese autocracy, and instead advocate cooperation on shared challenges.

China’s organic approach reflects its long history of managing systemic collapse and rejuvenation. This experience has shown that while top-down mechanical planning is useful, it must be combined with bottom-up implementation and adaptation. Rigorously monitored two-way feedback mechanisms ensure that national, local, and community goals are aligned, policy missteps are corrected, and micro-level behaviours that threaten systemic and social stability are checked.

When something is not working, Chinese engineers and planners act on leverage points – or “key entry points” (切入点) – for example, refining standards, incentives, regulations, information, or goals. When direct or “positive” (Yang阳) interventions fail, indirect or “negative” (Yin阴) approaches are employed. It is this open, experimental approach – which recognizes that the economy is a complex adaptive system – that enabled China’s economic miracle.

The point, as Meadows explained, is to “stay flexible.” After all, “no paradigm is ‘true,’” and “every one, including the one that sweetly shapes your own worldview, is a tremendously limited understanding of an immense and amazing universe.” Why limit ourselves further – and invite further gridlock and chaos – by clinging to zero-sum logic, binary thinking, and futile competition?

- Andrew Sheng is Distinguished Fellow at the Asia Global Institute at the University of Hong Kong and a member of the UNEP Advisory Council on Sustainable Finance. Xiao Geng, Chairman of the Hong Kong Institution for International Finance, is a professor and Director of the Institute of Policy and Practice at the Shenzhen Finance Institute at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2021.

www.project-syndicate.org