Weather overview for the fortnight to 09 June and short-term outlook to Wednesday 14 June 2019

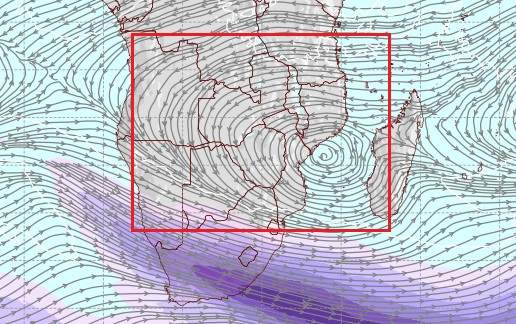

Visual: Jet Stream direction and velocity at 36,000 feet for Thursday midnight 08/09 June.

Source: GrADS/Center for Ocean-Land-Atmosphere Studies at George Mason University, VA.

Recent Developments

After two fairly uneventful Namibian weather weeks, conditions in the larger picture finally seem to be changing albeit at a snail’s pace.

The previous week saw a continuation of the very static mid-winter conditions that have been in sway since the second week of July. Over the previous weekend, there was a feeble attempt of some local intrusion from a cold front that had far more impact in the Western Cape than north of the Orange River. This past week, however, conditions settled back again to that all-too-familiar picture of cold nights, warm afternoons, cold days at the coast, and very windy conditions in the southern Namib.

The other remarkable feature of this winter, also repeated itself: – a fairly large and noticeable difference in ground-level conditions between the Karas region in the south and the northern regions along the Angolan border.

For the keen weather observer, this raises the issue of what is causing the winter to be so mild up to now. The answer lies in the visual, very clearly shown by the pronounced anti-cyclonic circulation in the upper-levels. The visual is based on observed conditions and as such offers a fairly reliable view of what transpires way above our heads.

The jet streams flow at altitudes above 30,000 feet. The visual shows conditions at 36,000 feet or 200 mB. This is indeed very high up, some 11 kilometres, and even above the altitude where jet-propelled aircraft normally travel. The formal divide between troposphere and stratosphere is at 30,000 feet indicating that 200 mB is right at the edge of the perceptible atmosphere.

Despite its height, surface (ground) level weather is almost invariable influenced by what happens in the stratosphere and the current Namibian winter is a textbook example of this. That anti-cyclonic circulation has an impact far wider than its immediate core. The red rectangle is an approximate indication of the sphere of influence that originates from this system whose core is located above the Mozambican Channel.

Two important local events are determined by the strength and the location of that upper air disturbance. The first is that it prevents the higher altitude impact from the Cape cold fronts to reach into Namibia, and the second is that the whole system consists of an enormous volume of air, over an equally enormous land surface area, that tends to sink once the warming effect of solar radiation starts to wane after about 14:00 every day. This produces the unseasonally warm afternoons across the entire area marked in the red box. In short, it is widespread high pressure control over a vast area of southern Africa, coming from atmospheric level so high up that it is difficult to believe what effect it has on the surface.

To try and understand this, imagine a column of air covering a land area of about 4000 (four thousand) kilometres by 2000 km, and then multiply this by 11 km deep, and one starts getting an appreciation of just how enormous these systems are. It follows axiomatically that the impact on the ground must be big simply because the entire system is so big.

Not until that upper-level anti-cyclonic control (which has been there for two months) disappears, will surface conditions change significantly from mid-winter to early summer.

On the Radar.

The windy conditions that set in over the interior during Thursday night had little impact other than rattling a few roofs and trees. While the temperature was slightly lower on Friday morning, for the reasons explained above, the effect was short-lived and conditions resumed their static stance by the afternoon.

Only in the southern Namib was it somewhat different with unstable conditions pushing a fresh wind up the escarpment and into the interior. Similar to the previous cold intrusion (in July), it was not a true frontal system but only cold Antarctic air circulated by the continental high pressure cell into Namibian airspace. However, when it reaches Namibia, it is roughly ten degrees warmer than when it entered the continent in the southern and eastern Cape.

The rapid migration of the continental high to the east ensures that the cold, windy condition stay for only one day. By Saturday, the departing continental high has severed its link with the South Atlantic high leaving space for a northerly airflow to resume and warm the Namibian interior.

The South Atlantic stays in situ over the ocean with a fairly strong core of about 1030 mB, roughly 1000 km offshore South Africa’s west coast. It is displaced to the north by about 400 km.

By Sunday afternoon and into Sunday night, the South Atlantic high makes landfall again, bringing cold overcast conditions to Oranjemund and possibly to Lüderitz and inland to Aus. This is a pattern we have often seen so far. Temperatures will drop rapidly in the Karas region during Sunday night and there is an outside chance it may go below zero in the Karasburg district. This depends to a large degree on wind exposure.

By Monday, the south-western quadrant will be cold in the morning up to the Gobabis district and the cold will come from the east as usual. Frost is not expected. The same high pressure cell that brings in the cold, also prevents it from travelling directly from the southern Cape to Namibia.

By Wednesday a weak trough develops along the northern Namib pushing in from southern Angola which should lead to windy conditions in the Kunene region, particularly over the coastal plain. Over the rest of the interior the airflow will revert to north which will produce warm to hot days from Grootfontein further northward.