Will you pay to become the owner of a kambashu? If not, then you do not belong in an informal settlement

The move to protect shack ownership in law is arguably one of the more exciting recent initiatives to unlock a vast source of funding for poor households. This entails a process, described by the Ministry of Land Reform as a pilot project to draft the broad outlines of a Land Tenure System for shack dwellers.

As any kambashu resident will tell you, life in the informal settlements is not easy. In Namibia, this is no different than the rest of Africa, or the rest of the Third World for that matter. Be that as it may, a family living in a shack in an informal settlement is at the very bottom of the economic food chain. These people are exposed to constant poverty and prone to exploitation and subversion.

Detailing life in a shack will fill many books because of its manifold dynamics. A struggle for daily survival is perhaps the most appropriate label to try and convey to middle class folks what grassroots realities are.

Nevertheless, I do not want to dwell on the painful realities of informal settlements but rather join the discussion around the ideas behind the Land Tenure System.

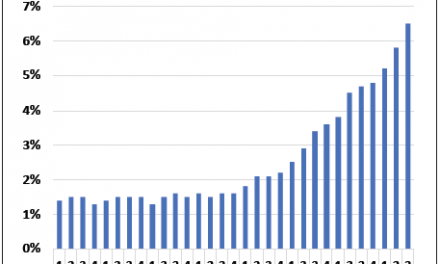

If one looks at the dynamic processes in an informal settlement, it is often amazing how these almost chaotic societies arrange themselves spatially and how perceptible upliftment takes place over time. Here it is wise to remember that whatever progress the informal settlement makes, is an arduous and drawn-out affair and meaningful change can only be observed over very long time spans, typically ten years or more.

There is no fundamental reason why this process should take so long but it should be obvious to any analyst that the rate of development is determined by the available capital, and here I mean capital in its broadest sense.

Since there is very but very little capital available for capital formation in the conventional economic sense, it implies that the labour of the residents, supplemented by very limited materials, is the main form of capital. Still, after a number of years, there is a very discernible difference between areas where the kambashus are five years or older, compared to those that have just been erected in the last year. The difference is even more noticeable in older informal settlements.

The point is, although they have zero to very little spare cash, kambashu owners scavenge for material, beg, borrow, and pilfer, but eventually a structure takes shape, becoming the prime form of shelter for the family. And as this process continues, by adding their labour capital, the kambashus consistently improve over the years until eventually, ten years later, it has become a proper dwelling.

This process can be sped up if more money was available to the family but the conundrum is that nobody in the formal economy wants to advance them any form of credit.

This is where the Land Tenure System comes in. If I read it correctly, the pilot projects in Oshakati, Gobabis and Windhoek, are designed to test the practical demands of registering ownership of a kambushe so that this right can be protected in law, turning the kambashu into a tradeable commodity, or a form of collateral for external financing.

This is not a new idea. If my memory serves me correct, the Cuban-born, US economist, Professor Carlos Diaz-Alejandro did some work in this regard in the 1970s.

When I first encountered the academic work that supported the practical execution of community-based financing schemes, I considered it to be a hairbrained idea. After all, from a conventional point of view, what form of security can a poor household in an informal settlement ever provide. Their existence is literally from hand to mouth.

But as Windhoek grew and its informal settlements became such a headache that the City had to intervene and bring some structure to the settlement process, I started realising there is much value in a kambashu and that value can be released, or liquidated, if there is some form of proof of ownership.

This is where Kambashu Dynamics come into the equation and I had to change my perspective to realise what enormous combined value is locked up in hundreds of thousands of kambashus all over Namibia.

Make no mistake, there is a lively trade in kambashus, only if you do not live there, you are completely oblivious to this dynamic. In Havana, a typical small, one bedroom kambashu changes hands for anything between N$3000 and N$6000. There is no shortage of offerings, neither is there a lack of uptakers. Kambashus are hot property and they trade like chocolate cake.

For the somewhat bigger, more mature kambashu, the price may go up to about N$9000. So far, I have not heard of a kambashu selling above this level. This is for a very simple reason. When a kambashu gets to that value, the township where it is located is approaching its tenth birthday. Over the years, both the area and the people have made upward progress through the cumbersome, labour-based process described above. It means that the area now starts bordering the dividing line between informal and formal settlement. So, for argument’s sake, let’s say the tradeable value of a typical early to mid-stage kambashu, does not exceed N$10,000.

Now tenure comes into play. Were the family in a position to apply for formal financing, they could raise anything from N$2000 to N$8000 as medium to long-term loans for which they can offer their home as collateral. This is not a lot of money for many people, but for thousands upon thousands it is a small fortune, and it may just provide the kickstart such a family needs to go another rung up the development ladder.

The main obstacle is proof of ownership. Here, I have also been completely dumbfounded over the years. Go into any informal settlement and start asking whose kambashu is this or whose kambashu is that, and you will be amazed at how accurately and openly ownership is acknowledged.

This is the whole secret to collateralising kambashus. The proof of ownership is community-based and it is so dependable that I still have to hear of a squabble over either land or home in an informal settlement.

Now I know the government wants to involve banks and wants them to recognise the validity of tenure records, specifically so that shacks can be accepted legally as collateral for credit, but in my mind this would kill the initiative because banks are not designed to go and prove ownership outside the formal, very structured concepts of ownership and its legal enforceability.

I believe the whole Land Tenure System must be delegated to organisations like the Shack Dwellers Federation. These informal groupings have the skills and the intelligence channels to determine ownership, and as financial administrators or conduits between capital and kambashu owners, they have the means and the savvy to determine exactly what belongs to whom.

I am not saying the Land Tenure System is dead in the water, on the contrary, my advice is that it should go ahead, but then we must take note of the lessons learned in Latin America’s favelas. It has been tried and tested there, and there is no reason for us to repeat the mistakes.

After all, if it is implemented in a practical, workable way, the outcomes are to the benefit of everybody, both the poor and the rich.