Are there any benefits in setting our own inflation targets?

Headline inflation is edging up, increasing incrementally from its low point of 3.5% in February. For three consecutive months it has risen very slowly but consistently and during May, the pace has also accelerated.

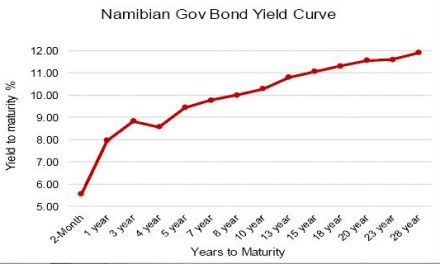

Some of the technical aspects of inflation I have covered in an earlier essay, so the intention here is not to drown in methodology and technicalities, but to consider policy and impact. Solid technical analysis can be found in the work done by groups like the Institute for Public Policy Research, IJG Securities and the PSG Konsult Group.

When looking at inflation policy for Namibia, essentially there are only two important questions. First, does Namibia have an inflation policy, and second, what is an ideal inflation target?

The answer to the first is a simple No, but inflation is far too complex to allow such a flat view. It will also not satisfy the need to understand the dynamics behind it, and the implications for monetary policy and for the broader economy. Nevertheless, there is no official inflation targetting that I am aware of. The Bank of Namibia infrequently refers to the South African target (which we can not ignore) but I have never seen it stated that it is also our target.

It therefore requires a broad overview of South African inflation policy to draw meaningful conclusion for our local case. South Africa set its inflation target in a band between 3% and 6% for so-called headline inflation. This was set shortly after Mr Trevor Manuel became the Minister of Finance in 1996, tasked with the almost impossible job of turning the sinking SA ship around. He saved their economy by focussing on the external value of the Rand, the exchange rate, and on inflation. This he achieved through a set of policies, among them gradual market liberalisation, and reducing budget deficits, and he achieved remarkable success. As part of the process, the South African Reserve Bank published a set target, the 3 to 6% band we still have today.

When that target was set, SA headline inflation was typically around 12% or higher. So the upper level of the band was not chosen as arbitrarily as many analysts argued. It set a real target of halving inflation, and then further reducing it to a level that was manageable for the economy, and bearable for the consumer. When this target was reached, his other problem, the Rand’s external value, solved itself.

This brings me back to us. Although we quote the SA target, even after 22 years, I could not find any formal work to determine a suitable level for the Namibian economy. We have simply “adopted” the SA target, mostly because of the Common Monetary Area agreement, and I believe, because a very substantial part of our inflation is determined by SA and not by local conditions.

Some of you may argue that a borrowed target is better than no target at all, but I want to emphasise the point that a local target will require some intense analytical work, keeping in mind our own development targets, before we can set a practical (achievable) target which will have a bearing on both monetary policy and local economic conditions. It must also not be punitive to the consumer.

Talking to several people who certainly have the capacity to appreciate inflation’s impact on growth and development, I was struck by the widespread opinion that inflation is what it is and there is very little we can do about it. Our monetary policy certainly does not have the clout to make much of an impact on local inflation. This, they say, was amply demonstrated last year when the government’s financial position had a much bigger impact on inflation, than any official interest rate benchmark.

Does this imply I am wasting my time discussing the need for a sensible inflation target? I hope not.

It is my fundamental view that inflation erodes wealth. It is fairly useless to post nominal growth rates of between 9% and 12% when we actually achieve very little after compensating for the corosive effect of inflation. Furthermore, its impact on businesses and on the government are far less severe because both have the flexibility to access financing, to manipulate prices, and to reduce operating costs.

A household does not have that luxury. It is a direct victim of inflation and its only recourse is to press for higher income, thus only continuing the inflationary spiral. But inflation is still the individual’s number one enemy, in the process of reducing spending power, also pushing the gap between the rich and the poor ever wider.

Is there a realistic target for Namibian inflation? I believe so.

When we look at economic growth from 2012 to 2015 and from 2016 to early 2018, it provides a pointer that despite stellar growth in the heyday of borrowed stimulation, growth could have been much better and sustainable, had we targetted 3% headline inflation as the upper limit. The same applies to the freezing period from 2016 onward – were inflation at 3% or below, the recession would not have been as severe and far more manageable.

Granted, this is also somewhat arbitrary but my view basically follows the same tactic Mr Manuel followed way back. Instead of trying to postulate an “ideal” inflation based on certain assumptions with which other people may or may not agree, I believe more can be achieved by looking at the medium-term history and asking what harm inflation caused when the gravy train was running full steam.

Based on those levels, I say headline inflation above 3% is harmful. Whether it is achievable depends on a myriad of factors, top of which are government interference and budget deficits. But what has been proven beyond doubt is that growth can be very misleading if excessive inflation follows in its wake. Above 3% is excessive.

(Featured graph courtesy of PSG Namibia Research)