Deflating the Namibian bubble will take several more years. The trick is how to reinstate growth without blowing new bubbles

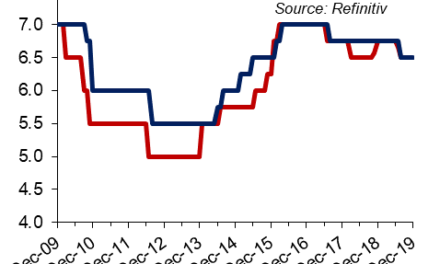

The economic damage of 2010 to 2015 is proving far harder to dismantle or reverse than what was previously expected. When the finance ministry’s so-called frontloading started in October 2016, the general expectation was for a semester of deflation after which the economy would revert to mean by itself.

That did not happen and 2017 turned out worse than 2016. With hindsight, the reasons are not difficult to spot and there is a long list of impacting factors, but I believe the single most important one is the unprecedented level at which the economy was inflated. This did not only come from the government’s side but was equally ambitiously helped along by credit extension from both banks and vendors.

The government has two main conduits for dumping additional liquidity into the financial system. The first is its wage bill and the second the state’s procurement mechanism through government tenders. There are a number of smaller streams like government pensions, running costs on consumables, consulting fees, PSEMAS, old age pensions, direct social stipends for certain target groups, and the social security fund but all these pale into insignificance compared to salaries and capital projects. And some of these originate from the wage bill source, at least from a Cost to Company point of view so they do not pose an additional financial burden on the fiscus but they certainly help bring more liquidity to the consumer side of the economy.

From 2011, the first year in which the effect of the 2010 stimulus showed up in statistics, fiscal income grew nominally by about 18% per year. This carried on until late in 2015 luring many government officials into the false view that this growth was generated by the economy. It was not, and this is the key point to grasp when lawmakers and policymakers have to make up their minds during this year to decide what level of artificial stimulus is required to prevent the ship from keeling over. The economy grew because money was borrowed to pay civil servants and pay for an ambitious collage of infrastructure projects.

Spotting, measuring and defining the extreme housing bubble is easy because it is so extremely out of sync with all other economic indicators. This will eventually turn out to be the most difficult bubble to deflate because it is structural. All the banks’ balance sheets are heavily overweight in mortgages, some as high as 44%. That is a scary statistic, and perhaps the most reliable indicator that disinflationary pressures will be with us for at least four years, but it can be as long as ten.

The second bubble is wages. One of the results of the expansion of the government was that many more consumers with means were created. This started an inflationary spiral that became ingrained in the Namibian economy for many years and from which we are still suffering despite the significant and obvious correction which became visible from February last year. Government increments continued to outpace inflation for at least five years, only stoking more inflation in its wake as more and more demands were made for higher wages and for more entitlements.

I still remember being asked in the first month of the current administration, how much I thought the old age pension would go up. I worked out a few basic calculations and said I believe not more than 15%, max 20%, but if it were to be more, we are headed for serious trouble. As it turned, out this single entitlement channel went up by 50%. The actual demand on the fiscus was not large simply because there are not that many old people and disabled people in Namibia, but the signal it released was all important. It send out a message that the all-powerful capital market is the widow’s pitcher and that there is no end to the available credit. Elevated wage demands, entitlements, and social support became the norm. You simply had to ask to get.

By far the most important bubble is the one we created in construction, excluding private housing. With all the new buildings, roads, dams, harbours and other infrastructure projects, this sector became the single biggest driver of additional public investment. With this we all too familiar. The tender mechanism became the goose that laid the golden eggs and noveau riche millionaire tenderpreneurs proliferated faster than the biological population growth rate.

What we have today is a pervasive, massively inflated bubble which, for lack of a better description, I call the Namibia Incorporated bubble. In short, this translates to the observation that the entire Namibian economy is inflated, not only the more painful and visible sectors I mentioned above. The easiest way to make a reliable comparison and to measure the size of the bubble is first to measure local productivity against South African productivity, then compare their incomes to ours, and then to make a cost of living comparison. From a macro perspective, all three point to only one thing- the whole Namibian economy has become a bubble, out of proportion with all conventional means to measure the pace of growth and the return on investment.

And nowhere is this more clearly displayed than in the six back to back quarters of contracting Gross Domestic Product. If the economy were not inflated out of all proportions, the adjustment would have been brief and decisive. The fact that the malaise continues is the number one macro-economic indicator that we have forfeited future growth for the sake of six wild gravy train years.

The only riddle we now need to solve is how to disinflate the super-sized bubble without popping it. There is no easy answer to that twisted knot.