When a 500-year-old painting is worth more than a whole African country

It is painful to be confronted with the reality of Africa’s insignificance. Earlier this week Africa made headlines again, but for all the wrong reasons.

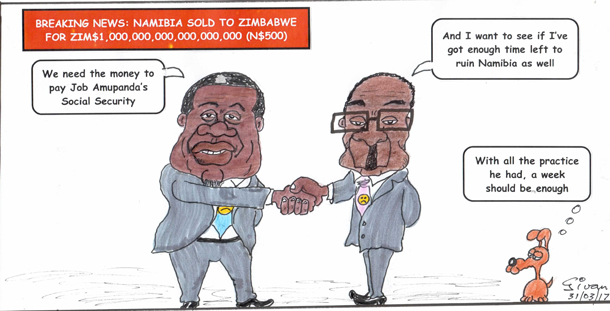

When Mugabe’s military commanders decided they have had enough of the nanogenarian’s wife-induced antics, they gave the command and a not insignificant mobilisation took place. Tanks moved into Harare and by Wednesday it seemed the old fox was toast. International media was slow to pick up on the Zimbabwe developments and it was only by Thursday that we were able to separate fact from the barrage of nonsense doing the social media rounds.

However, that same day the Zimbabwean military moved on their leader, a supposedly Da Vinci original painting was sold by Christie’s in New York for a horrendous amount, I believe in the order of US$450 million or so. That juicy item was immediately picked up the wire and splashed as a headline on all the major international publications I follow.

Now, the most revealing aspect of these two world records was the inferior position of the African event on front pages and on websites. The fact that Salvator Mundi fetched more money than what we need to balance our budget, was reported with far more prominence than the fact that seemingly, Africa has rid itself of a tenacious hooligan, and that is was accomplished by his own people. This downranking of a very important and significant African event, showed just how little we matter in the eyes of the West.

For several years, we have been bombarded about Africa being the continent of the next fifty years and how much capital must still be invested in the economy. That was when India and China still had a roaring appetite for our minerals and when oil pumping nations enjoyed the support of an elevated crude price. Then commodity reality set in, prices dropped and before you knew it, dozens of African economies were in trouble, including the big ones in South Africa and Nigeria.

The talk about real growth rates across the continent of 5% and above, even 7.5%, suddenly evaporated, and we were back to being a basket case. Everywhere, fiscal incomes were under pressure, and everywhere debt suffered. So did governments and ordinary Africans.

Meanwhile, all our aches and ails remained including a despotic neighbour who lost his cortex in a mopane worm attack.

When things started boiling over in Zim, I thought this will be world news for as long as the tete a tete among the leaders continued. Not so! Within less than a day, the most important political development on the continent was overshadowed by the news of an individual who can afford to fund our budget deficits, rather opting to put all this money in an art relic, the originality of which it seems nobody in art circles agree about.

I have no real qualms about the extravagant art collector, after all I assume it is his or her own money that was spent. The glaring inequality of it all also does not upset me too much. We have become used to being the world’s discarded region. But the fact that the change of hand of a 500-year old painting is more newsworthy than the riddance of an annoying fart who has enslaved 14 million of his own people, that really upset me.

What is there we can do to change the African stereotype and the world’s general view of us?

Unfortunately, not much. For as long as we tolerate such injustices as what continues to happen in Zimbabwe seventeen years after it started, for so long the world will ridicule us.

On diplomatic functions we are received with feigned genteelness and civility, but behind our backs international leaders shake their heads while concocting another deal that will exploit our resources with very little left for us. And it is all papered over by a universal perception that we allow ourselves to be abused by our own leaders, so why should not the rest of the world also jump in and take what they want.

Sometimes, when I perceive the ubiquitous opinions by which we are automatically downgraded to second class world citizens, I cringe. And when I see how we live with injustice simply because of our overdeveloped sense of piety and submission to abusive leaders, then I realise we are responsible ourselves for the view the world holds of us.

There is one consolation though. By Friday Zimbabwe was still in the news while I really had to hunt to retrieve the Salvator Mundi. It seems in this case, good news is still selling.