Money everywhere is getting cheaper, except in Africa

Without going into the technical detail of how investment capital is valued, it is safe to say money is getting cheaper. The most obvious indicators are long-term interest rates in developed markets, and the anxious search for yield by investment managers across the world.

In a conventional scenario, cheaper capital will by definition imply a lesser value, which should translate into inflation and then hyper-inflation. However, the reverse is taking place. As long-term interest rates continue to edge lower, especially since February this year, inflation in the USA, Europe and Asia remains very subdued, with many analysts actually fearing the world is at the start of a disruptive disinflationary phase.

A practical benchmark for local investors would be investment returns but this is a vague and somewhat technical concept. Return on investment and yield are not strictly the same thing and many people whose business it is to generate returns for other people, simply talk about returns. This includes a range of benchmarks and metrics but it all boils down to what the retail investor gets back for his buck, either at scheduled intervals, or upon maturity.

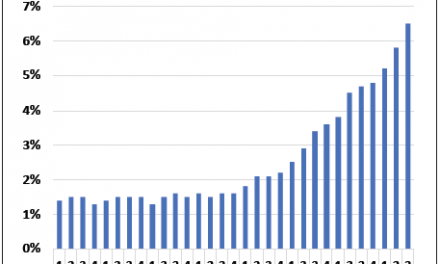

Long-term interest rates in developed markets are at historic lows. The US benchmark rate, the 10-year treasury bills, have consistently come down translating into a shrinking yield and a lesser return for investors. Still, there is no lack of investors and it remains the world’s most-traded and invested capital market instrument. Following the Brexit vote, it has also gone to historic lows but has settled around 1.5% recently. But it is still a long way from the customary 4% yield. The same scenario repeats itself with all other long-term government paper. Interest rates in Germany has gone negative, in Japan they have been negative for a long time, in the UK they are below 1% while the 2-year note went negative immediately after the Brexit vote, for the first time in history. Even Aussies come away earning less than 2% on their government debt instruments.

It is dirt cheap to borrow in developed markets, that is if the businesses looking for credit can convince the banks they are worthy candidates for financing. At this point, only governments benefit from these incredibly low rates. They now only have to pay a fraction of the interest they used to pay and in Germany and Japan, the investor pays the government for the privilege of holding its paper.

If that does not smack of deflation, then there is something wrong with its definition in text books.

Since Africa as a continent is so far removed value-wise from developed markets, why is it that these generous rates do not show up on our local bourses. Southern European governments pays so much less for their public debt than African governments, even if they are borrowed to the hilt, and in my view, pose a much bigger threat to the stability of the world’s financial system than all African countries put together. Would it not have been a boost to our economic development if our governments could borrow at 2% (Australia) or between 3 and 4% (Greece). What bigger risk is there in an African country than in Greece?

Looking at these incredibly low rates, it makes no sense at all why most governments in southern Africa must borrow between 8 and 12%.

I believe that the world’s investment capital is under enormous deflationary pressure. I support my views by looking at long-term instruments. I also believe that any investment in developed markets is bound to reduce in value over time.

Alongside these observations and expectations, I take note of the new narrative regarding the continent as the future investment haven for all those institutional funds that only need to find a space for a few billion here and a few billion there. Part of this narrative is the talk about our young population, our natural resources and the vast potential for future investment and development. While all this is true to some extent, the real underlying motive for viewing Africa in such a changed light, is the desperate search for yield. And since Africa’s contribution to world GDP is so meagre, I believe there are scores of investment managers out there cringing when they have to explain to their investors in turn, why they must pay the German government for the privilege of buying Bunds. They look at us and they see these substantial returns compared to their own either very low returns or negative returns.

This is also why I expect our development trajectory, at some point in the not too distant future, to cross the cusp and to explode financially.