GDP estimates have the power to hide all kinds of sin

The Medium Term Expenditure Framework is an invaluable tool to manage our national finances. It provides a three-year look into the future, and it offers a reconciliation of sorts of the two preceding years. These figures reveal, on a macro-economic level, what goes on in the minds of the government’s financial planners, specifically those who are tasked to implement government policy using the budget as the instrument.

But the Medium Term Expenditure Framework is also much more than just an updated take on what transpired. If one know where to dig, it reveals a whole set of underlying assumptions and it offers the outline of the broad model that forms the background to the rest of the more detailed planning.

The latest budget is no exception, and since we have now established a remarkable depth in the budget process compared to when we adopted the Medium Term Expenditure Framework in 2003, it must be assumed that the figures as they are presented, indicate much reflection and consideration of real outcomes.

In the budget, the income projections are fluid. They are not pretending to be anything else which I assume is the reason why the minister goes to such lengths to explain their view and expectation of the economy.

Income projections can change as the future unfolds. It is almost axiomatic that the real outcome will be different from the projected one. This, in turn, is the reason why we get national accounts, although they are largely academic when they are released some seven months after the event, i.e. the conclusion of the previous financial year.

The expenditure side of the budget is, of course, an entirely different matter. What the government intends to spend is the only known factor when the budget is tabled. It is an expression of government policy and it is the signal from the Ministry of Finance to the other ministries and agencies that this is the amount of money each has available. The outcome of expenditures is far more certain than that for income.

But this conflict between estimated income and real expenditure, often creates some surprises, some which can be welcome, and some which can be downright nasty.

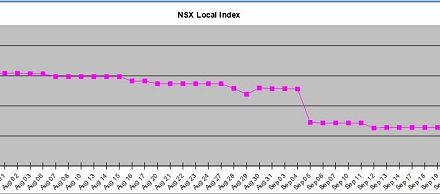

For instance, in the period from fiscal year 2013 to 2017, the Gross Domestic Product projections converged to just below or just above 10% annual growth. This is very clearly embedded in last year’s MTEF and can be calculated by any person with the inclination to crunch numbers, and a suitable calculator.

The outlier in the previous series was the 2013 GDP estimate which bargained for a 14.06% nominal GDP increase from the previous year. This did not happen. In fact, the nominal increase was only 11.07%, also a fact that can be readily verified by a few simple calculations. What it shows is that 2013 also tended towards the 10% benchmark adopted for the rest of the MTEF.

I think it is not far-fetched to say the government regarded a 10% annual GDP increase as a realistic figure on which to base all the other ratios.

However, the new MTEF throws all of that overboard. Suddenly the assumed nominal GDP growth increases to 13.45% (2015/16 but still an estimate), 14.12% (2016), 16.06% (2017) and 15.84% (2018). These rather significant adjustments beg a few serious questions.

On what basis does the Ministry of Finance believe nominal GDP will grow between 14% and 16% over the four years from 2015 to 2018 when the actual outcome for 2013 clearly shows the then projected 14% growth only came to 11%. From the GDP estimates in last year’s MTEF, the latest set has been bumped up by 5.41% and 9.97% respectively for 2016 and 2017.

In my mind there is no logical explanation for this adjustment and current conditions certainly do not merit such a significant improvement in the expected GDP growth.

I believe the answer is hidden in the expenditure side of the balance. Total expenditure for this year is budgeted only 0.885% higher than last year, a feature that showed up, albeit it not as severe, in last year’s MTEF. But expenditure for 2017 is set to grow by 5.85% and by an uncomfortable 6.53% in 2018.

Given the constraints on the fiscal side which have manifested itself since October last year, there is only one way to hide the growth in expenditure. Bump up the GDP figures to camouflage the growth in expenditure, then it does not look so bad on paper, expressed as a ratio of GDP. There is a strong correlation between the GDP adjustments from last year to this year, and the budgeted expenditure for the new MTEF.

If last year’s projections prove to be more reliable, then the deficit will be substantially higher than what the MTEF now presents.